- New study maps priority areas for conservation in the Sundarbans Biosphere Reserve with species-wise zonation.

- Mangroves are vital ecosystems that help in carbon sequestration, coastal protection from cyclones, harbour rich biodiversity and are a source of livelihood for local communities.

- Mangroves, and wetlands in general, are increasingly disappearing from the world due to anthropogenic pressures and sea-level rise.

- Despite a few shortcomings, the study model can be replicated worldwide to enable contextual and specific mangrove conservation measures for each region.

A new study published in Scientific Reports has mapped priority areas in the Sundarbans Biosphere Reserve (SBR) that are highly suitable for mangrove conservation and restoration.

The Sundarbans Biosphere Reserve is spread across 9,630 sq. km., of which 4,266 sq. km. is under mangrove forests. It is the world’s largest single block of mangrove and “is highly threatened and drastically reducing at an alarming rate due to the overexploitation of resources, land transformation for aquaculture practice, increase in paddy cultivation, infrastructural development, and human settlements,” according to the study.

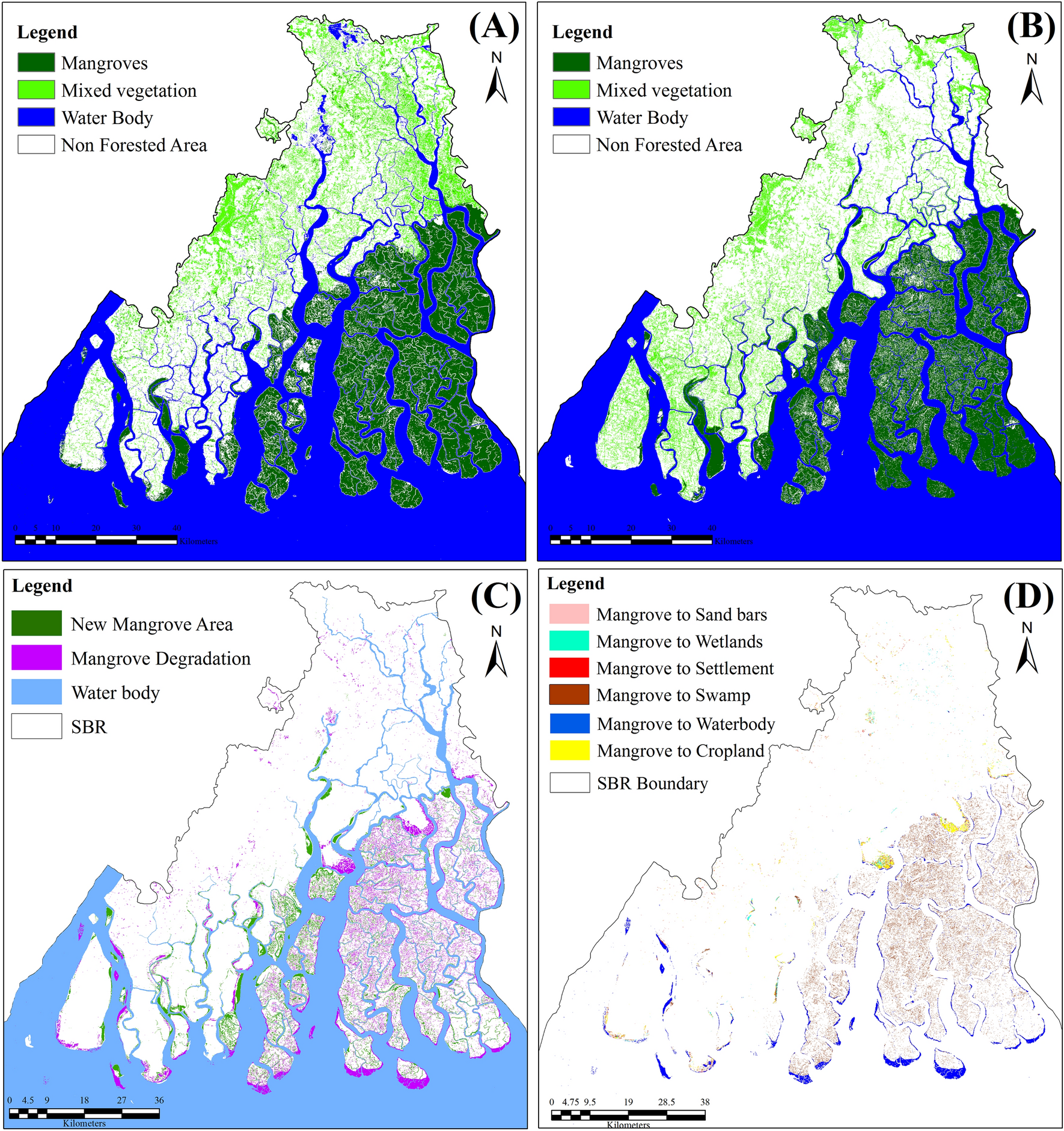

For the study, researchers from the University of Manchester, Jamia Milia University, New Delhi and World Wide Fund for Nature India (WWF-India) assessed the habitat suitability for 18 true mangrove species in the Indian Sundarbans, using 10 machine-learning algorithm and field-based occurrence data. They identified areas covering a total of 1,203 sq. km. for prioritising restoration.

Nearly 13% of this area was found under uninhabited islands and 87% area was found within the human habitat islands, Mehebub Sahana, from the University of Manchester and one of the study authors, explained to Mongabay-India. “We have also prepared a species-specific recommendation for the restoration of mangroves to reduce the impact of climate change and cyclones,” he said.

“This is the first article that tried to prepare species-specific mangrove restoration recommendations,” Sahana added. The findings of this article will scientifically enhance current restoration efforts in the Sundarbans and can be replicated around the world.

Commenting on the scalability of the study model, R. Ramasubramanian, director of the coastal system research programme at the M.S. Swaminathan Research Foundation (MSSRF), Chennai, said, “Species-wise zonation can be understood over a large area like Sundarbans easily using remote sensing technology.” Based on the species distribution, planting of species can be undertaken. While the methodology is useful for mangroves of large areas, which are rich in diversity, it may not be of much use for smaller mangrove areas such as Pichavaram in Tamil Nadu, which have only a few prominent species.

“Such studies of assessing the suitable habitat of mangrove species for prioritising restoration, are very much required,” said Kathiresan Kandasamy, a mangroves specialist at the Annamalai University. “It sheds new light of academic interest on advanced knowledge of machine learning.”

However, there are some drawbacks, Kandasamy pointed out. For instance, the study is based mostly on secondary data, and not on field ground-truthing. “Studies should be mostly based on ground-truthing data in consultation with the practical knowledge of field workers and native wisdom of local people of mangrove areas such as Sundarbans, for a more reliable, practical and user-friendly approach,” he said.

He also added that the methodology is advanced and would be difficult to be used directly in the field by local people, field forest staff and coastal managers, without training and capacity building about machine learning.

Read more: India budgets for mangroves and wetlands

Disappearing mangroves

Mangroves are vital natural ecosystems, from protecting coastal ecosystems against natural hazards such as typhoons, to being a storehouse of rich biodiversity, helping in carbon sequestration and serving as a source of livelihood to local communities.

Yet, they are under constant degradation due to human-induced disturbances and climate change. A recent study of mangrove species around the world revealed that 16% of mangrove species are on their way to extinction and another 10% are under threat of degradation.

India has 4,975 sq. km. of mangroves forming 0.14% of its total area, which are under threat. The study area, the Sundarbans, has the largest halophytic mangrove forest in the world and is spread over Ganga-Brahmaputra and Meghna delta. The Indian Sundarbans Biosphere Reserve (SBR) is a “significant ecological region due to its luxuriant mangrove forest and high biodiversity,” the report said.

As elsewhere in the world, the area under Indian mangrove forests too has sharply declined during the last few decades, according to the study. The reasons include sea level rise, sudden natural disasters, over-harvesting, aquaculture expansion, shrimp and salt farming, regular oil spills, and lack of sustainable adaptive strategies. In the Sundarbans, nearly 76% area under the mangrove species Heritiera fomes has declined between 1959 and 2005, while other dominant mangrove species, such as Ceriops decandra, Excoecaria agallocha and Xylocarpus mekongensis are also rapidly declining.

Despite several mangrove restoration programmes over the last 50 years, mangrove conservation has achieved limited success in India. Ramasubramanian, however, sees an overall improvement. In recent years, mangrove conservation and management resulted in a gradual area increase throughout the coast except in few places like Muthupet in Tamil Nadu where there was a decrease in the mangrove extent of about 4 sq. km. after the 2018 Gaja cyclone, he said. Similarly, there was a decrease of 33 sq. km. after the Indian Ocean tsunami in the Andamans between 2003 and 2009, he said, citing the 2019 Forest Survey of India.

“Overall, the mangrove extent has increased due to conservation and management,” Ramasubramanian. “However, due to disasters, the mangrove extent is declining marginally which will be slowly covered. If there are repeated disasters due to climate change, there is a possibility of further reduction,” he said.

Kandasamy added that mangrove conservation in India is inefficient due to a non-ecosystem-based and non-participatory approach, without involving local people and key stakeholders in conservation. “Protection of existing forests should be given the top-most priority rather than planting. Indiscriminate planting without considering the ecological requirement of the species leads to failure,” he said.

A major constraint in studying mangrove species is limited information on their habitat distribution, the study authors say. The lacunae are being partly filled with geospatial technology that provides comprehensive, reliable, and up-to-date information on forest dynamics. In tandem with geoinformatics is computer modelling, where species distribution models (SDM) help identify suitable present-day and future habitats, and machine learning-based spatial analysis helps map, conserve and manage endangered, threatened, and vulnerable species.

Read more: Remnant mangrove tree sites show faster recovery post 2004 tsunami in the Nicobar Islands

Spotlight on mangroves and wetlands

Mangroves, and wetlands in general, have been the focus of three recent UN conferences in 2022. These include the 27th Conference Of Parties (COP27) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in Egypt in November 2022, which saw the launch of the Mangrove Breakthrough Initiative, co-led by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) in collaboration with the UN High Level Climate Champions, which set out to secure 15 million hectares of mangroves globally by 2030.

Coinciding with the launch of the Mangrove Breakthrough initiative at the climate COP27 in November 2022, another adopted resolution focussed on the importance of mangroves for biodiversity, carbon capture and coastal protection.

The 14th Conference Of Parties (COP14) to the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, held in Geneva, Switzerland (physical) and Wuhan, China (virtually) also in November 2022, launched a new Ramsar Regional Initiative that focuses on mangroves and coastal blue carbon ecosystems and aims to build regional cooperation for conserving these ecosystems. There was also a proposal to set up a new International Mangrove Centre in China, in cooperation with the Global Mangrove Alliance to ensure complementarity of efforts. The COP14 passed a Wuhan Declaration that pledged to, among others, “enhance the conservation, restoration and sustainable management of wetlands, and do so especially for wetlands that serve as habitats for migratory, threatened and endemic species, and those that play a major role in water cycle as well as encourage priority conservation and management of vulnerable ecosystems such as peatlands, coral reefs and seagrass beds, mangroves, highland wetlands and subterranean wetlands.”

At the 15th Conference Of Parties (COP15) ot the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (UN CBD) held in Montreal in December 2022, the United Nations University co-hosted a side-event on mangrove restoration which discussed the challenges and opportunities for mangrove conservation and restoration as a nature-based solution to climate change. At the event, Badiah Achmad Said, from Indonesia’s Ministry of Environment and Forestry said that preventing mangrove degradation would reduce emissions from land use by 30%. Meanwhile, the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) is collaborating with Brazil, Indonesia, Mauritius, Mexico, Myanmar, Oman, Palau, the Philippines, and Vietnam, to enhance capacity and develop models for mangrove restoration and sustainable management.

India is making special efforts to get international recognition for its mangroves and wetlands as well. India announced a programme for mangrove plantation in its 2023-2024 budget: the Mangrove Initiative for Shoreline Habitats & Tangible Incomes (MISHTI) under which mangrove plantation will be taken up along the coastline and on salt pan lands, wherever feasible, through convergence of MGNREGS (Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme), CAMPA (Compensatory Afforestation Fund Management and Planning Authority) Fund and other sources.

Read more: The reality of saving young mangroves in the Sundarbans

Banner image: An aerial view of the Sundarbans mangroves in Bangladesh. Photo by Touhid biplob/Wikimedia Commons.